Jellyfish Explained: A Guide to Jellyfish in Cornwall and the UK

Credit: Pedro Szekely

Words by Lydia Paleschi

This week we caught up with Doctor Victoria Hobson and Professor Stuart Bearhop at the University of Exeter’s Bioscience Department to get the lowdown on jellyfish, including which ones you can expect to see off the Cornish coast and how to stay safe in the water. We’ve answered all of the questions you sent and provided an overview of the species found in Cornwall to help you to swim in confidence. You can leave a comment at the bottom of this post if there’s anything else you would like to know.

To find out if there are jellyfish sightings in your local area, visit the Marine Conservation Society. They have a jellyfish watch so people can report their sightings and a map with recent sightings on.

Jellyfish in Cornish Waters

There are several jellyfish species that occur regularly in Cornish waters plus a few odd closely related things. The good news is, most of them are harmless and there are only a couple of species which sting. We outline the identifying characteristics of all of these species below.

Moon Jellyfish (Aurelia Aurita)

These are the most common jellyfish and we have been seeing a huge amount of them lately. Recognisable by four purple rings (sometimes more), the rest of the jellyfish is transparent. The aurelia have very short tentacles and reach up to 40cm across, though are usually much smaller. Their tentacles are around the edge and about half a centimetre in length so are difficult to see in the water. Usually found between April and September, Moon Jellyfish have a mild sting but you’re unlikely to feel it. You should have no problem swimming amongst these and Dr Hobson lets her young children relocate them from the beach to rock pools.

A Moon Jellyfish is characterised by four purple rings, a translucent bell and short tentacles. Credit: Amy Lewis for The Wildlife Trust

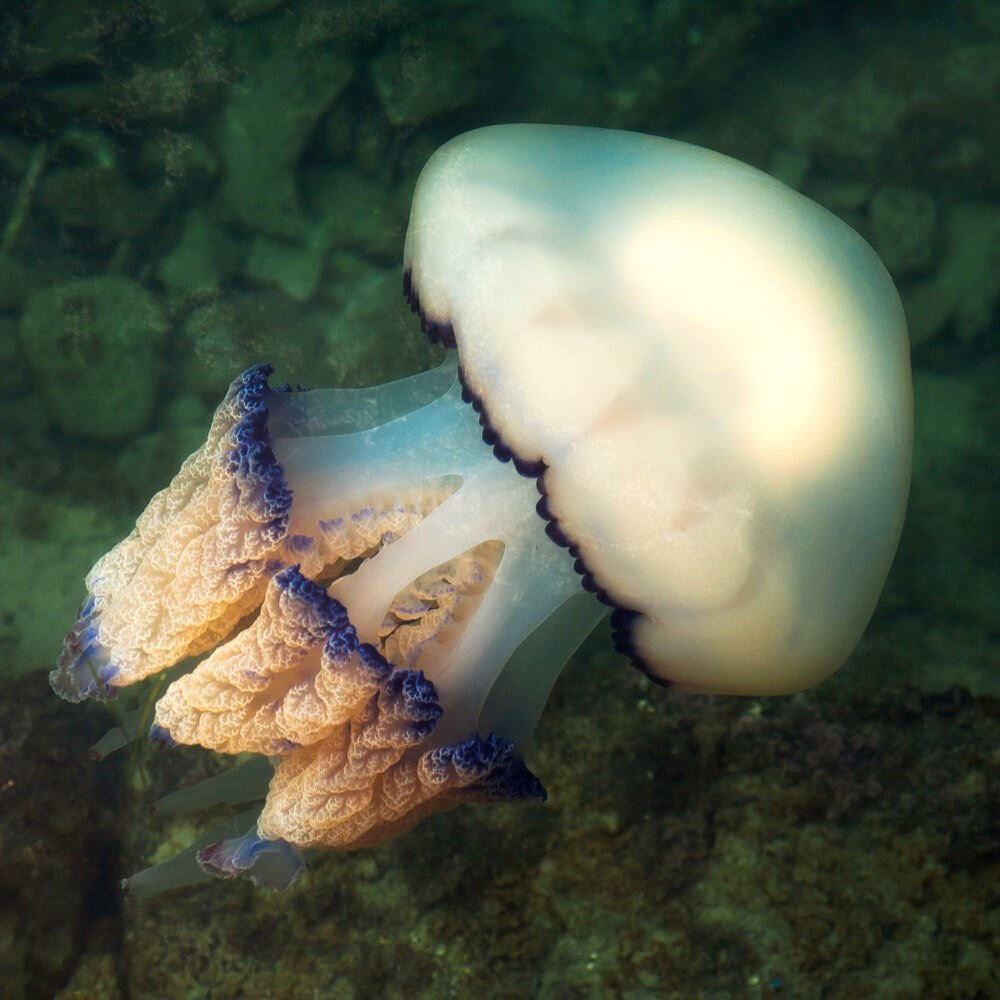

Barrel Jellyfish (Rhizostoma Pulmo)

The largest of the species found in UK waters, Barrel Jellyfish are off white in colour with purple lobes around their edges and can reach over a metre in diameter. They are known to actively swim away from movement in the water, so are likely to avoid swimmers. Instead of tentacles, they have eight oral arms which they take plankton in through. Found all year round, they are most abundant between July and September and don’t have stingers, however prolonged exposure to them can cause an allergic reaction a bit like a nettle sting. These pose no risk to swimmers.

Barrel Jellyfish are off-white in colour with purple lobes around the margin and can reach over a metre in diameter. Credit: Ales Kladnik

Compass Jellyfish (Chrysaora Hysoscella)

The compass jellyfish can reach up to 50cm in diameter and has a distinctive radial pattern on the bell which resembles a compass rose. They’re a translucent whitey-brown and have 24 longer, finer tentacles dangling from the margin and four frilly mouth-arms trailing from the inside. Again, these move away from people in the water, but they can sting and are best to be avoided. You’re likely to see these between July and September, though they are far less common than Barrel, Moon and Blue Jellyfish.

The compass jellyfish can reach up to 50cm in diameter and has a distinctive radial pattern on the bell which resembles a compass rose

Blue Jellyfish (Cyanea Lamarckii)

Blue jellies have a translucent body with a deep purple colour inside. They are small, reaching up to 30cm across and have long tentacles. Much less common than the barrel and moon jellyfish, these have masses of tentacles and are stingers. However, they give a mild sting not much worse than a nettle, which again is nothing to worry about. They are uncommon, but sometimes appear between April and July.

Translucent body with a deep purple colour inside. The Blue Jellyfish are small, reaching up to 30cm across and have long tentacles.

Lions Mane (Cyanea Capillata)

Lions Mane can reach up to two metres in diameter, but are usually much smaller. Their colour varies from yellow to deep red as their age increases. They have a bell margin with eight lobes and eight clusters of up to 150 tentacles each, which trail behind them like a mane, and the tentacles are longer than the oral arms. Lions Mane is a cold water species and it would be surprising to see them as far south as Cornwall. According to Doctor Hobson, if someone thinks they’ve seen a Lions Mane down here, they’ve more than likely seen a brown variation of the Blue jellyfish. More likely to be found in North Wales, Dublin and the Irish Sea, the Lions Mane does have a horrid sting to enable them to catch fish and smaller jellyfish.

Lions Mane have a bell margin with eight lobes and eight clusters of up to 150 tentacles each, which trail behind them like a mane

Crystal Jellyfish (Aequorea victoria)

Crystal jellyfish are beautiful, clear white translucent with fine lines coming out from the centre. They are rarely seen in the UK, other than off the coast of Cornwall. They are known to glow in the dark and can eat jellyfish bigger than themselves. Again, they have a mild sting.

Crystal jellyfish are beautiful, clear white translucent with fine lines coming out from the centre

Portuguese Man-o-war (Physalia Physalis)

A Portuguese Man O War is easy to identify as they are deep blue/ purple in colour and have an air filled ‘sack’ which floats on the surface of the water. Not a true jellyfish, it’s actually a hydrozoan, a colony of four different species. The balloon is one organism, the tentacles are another, the reproductive parts are another and the parts that eat are another. There is still a lot that’s unknown about how they work together or reproduce. What is known, however, is that their sting is nasty (in rare cases fatal) and that they have long tentacles. Even if their tentacles become detached from the balloon or they’re washed up dead on the beach they still sting. They’re normally autumnal and come when south westerly storms blow them in from the Atlantic. You’re more likely to see these on the North Coast but can get them on the south coast too.

For the full details on Portuguese Man o’ War, check out our blog Portuguese Man o’ War: The Facts.

A Portuguese Man O War is easy to identify as they are deep blue/ purple in colour and have an air filled ‘sack’ which floats on the surface of the water

Q & A: Your Questions Answered by Professor Bearhop and Dr Hobson

Are there any reasons I shouldn’t go in when there are jellyfish?

“Generally speaking, no. It’s personal preference of whether you go in or not. I would take my girls down to the beaches and let them relocate moon jellyfish from the beach to rock pools and they’re three and six years old. I’ve swum through moon jellies before and it’s been fine. If you see a Compass jellyfish I wouldn’t go searching it out, but even if it stings you it’s still likely to be mild. Unless you’re unlucky and have a bad reaction, I can’t see that a jellyfish sting would be any worse than stepping on a weaverfish.” (VH)

Are there any species I should be concerned about?

“The only species to be concerned about as a swimmer is the Portuguese Man o War. These are in a different group to the ones outlined above and can produce quite severe reactions in humans, they can have very long tentacles extending out from the float and main body. These occur in small numbers most years and usually in the autumn. However in some years they are extremely abundant.” (SB)

What should I do if a jellyfish stings me?

The NHS provides guidance on what to do if you are stung by a jellyfish.

What are jellyfish?

“Jellyfish come under a group called cnidarians and are invertebrate multicellular beings. They’ve been around for approximately 500 million years since the dinosaurs and are one of the earliest life forms that formed in the oceans. They eat a variety of different things from plankton to fish. Generally the more vicious the sting, the bigger the thing they eat. For example, the Portuguese Man-o-War eat fish so they have quite a nasty sting to immobilise their prey, whereas things like the moon jellyfish eat plankton so they don’t need a nasty sting.” (VH)

Where do they fit into the ecosystem?

“Increasing numbers of jellyfish can have quite a big impact on the health of the oceans and the fish populations. Problems have come from us taking lots of fish out of the ocean and so now there’s lots of room for jellyfish to exploit that niche. Whereas fish may have eaten some of the smaller jellyfish to keep numbers in check, reduced fish stocks could mean an increase in jellyfish.” (VH)

Does that mean there are more jellyfish today than there used to be?

“It’s difficult to know whether we are seeing more or less jellyfish today because people can report them more now. Generally the numbers wax and wane from year to year. It is normal for jellyfish numbers to peak during summer and autumn which is why we’re seeing lots of them at the moment.” (VH)

How has climate change impacted jellyfish?

“Jellyfish are very good at exploiting their local environment. When the environment isn’t as optimum, they’re robust enough to keep going. When there’s less food they can shrink in size and when there’s more they can grow. Climate change isn’t phasing them and they’re able to exploit the niches opened by the negative impacts of climate change on other species. Most jellyfish have a polyp stage to reproduce. The larvae can settle on surfaces and stay in that state for a very long time until conditions are right. They can lay dormant until fish stocks increase or algal blooms take place, though lack of research means there’s lots more to discover about their role in the balance of ecosystems.” (VH)

How long do they live for?

“We don’t really know how long they live for or whether they can survive over a winter. We have heard anecdotally of fishermen pulling jellyfish up from deeper waters during trawls in February so suspect they enter into some sort of rested state over the winter, but at this point we don’t really know. This would also be different for various species.” (VH)

Do they emigrate?

“We think that jellyfish stay actively in a particular area. Whether there is some movement locally, for example from the south to the north coast of Cornwall, we are unsure. It’s unlikely they cover long distances on a big scale, other than if they’re transported via a storm, however we can’t be certain. There are differences genetically between species from various parts of the world, which lends towards this hypothesis.” (VH)

How do jellyfish sting?

Jellyfish stinging cells are like a harpoon. When they’re triggered the harpoon fires out and administers the toxins. On the first touch only about a third of them will fire, so even when tumbled through the surf some but not all may be activated. This means that even if they’re washed up dead they can still sting, though it is likely to be less severe. Mainly the stinging cells are found on the tentacles, but with barrel jellyfish there are stinging cells on the mucus as well. The top of the bell is generally fine and it’s rare that humans can feel their sting, but I still wouldn’t recommend touching them at all.” (VH)

Why do some have long tentacles and some have short tentacles?

“Generally plankton eating species have shorter tentacles and fish eating ones have longer ones.” (VH)

If you have any more questions, please comment below or email wildswimmingcornwall@gmail.com and we’ll find the answers!

If you enjoyed this blog, why not sign up to our newsletter?

And if you know someone else who would enjoy it, please share it with them via email or social media.